Just Musing: Washington Mews.

“The ideal of quiet and genteel retirement, in 1835, was found in Washington Square, where the Doctor built himself a handsome, modern, wide-fronted house…

I do not know whether it is owing to the tenderness of early associations, but this portion of New York appears to many persons the most delectable. It has a kind of established repose which is not of frequent occurrence in other quarters of the large, shrill city….”

-Henry James, Washington Square

While approaching Greenwich Village’s Washington Square Park from the north, one can’t help but notice the cobblestoned street that runs between 5th Avenue and University Place and which seems to be frozen in time from an earlier era. A quaint street; hardly wider than an alleyway— she’s lined on both sides by low rows of historic carriage houses…and she’s called Washington Mews.

While approaching Greenwich Village’s Washington Square Park from the north, one can’t help but notice the cobblestoned street that runs between 5th Avenue and University Place and which seems to be frozen in time from an earlier era. A quaint street; hardly wider than an alleyway— she’s lined on both sides by low rows of historic carriage houses…and she’s called Washington Mews.

“Mews?” Youze ask!? Yes “Mews!”

“Mews” is an old British term that simply described a row of carriage houses with storage on the first story (space to store one’s carriage/coach, horse, and related bits and pieces) and which featured living quarters on the upper floors. Often situated behind city dwellings and often narrow in character, mews offer a window into a time when horses provided the main means of transport.

A Brook Runs Through It

A Brook Runs Through It

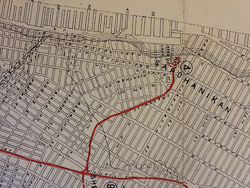

Long before the locals had any need for mews, a stream ran across what is today Washington Square Park. An Indian village known by the name “Sapohanikan” (or, Tobacco Field) occupied the area prior to 17th-century Dutch acquisition—and the villagers called the stream Minetta Brook. As the Dutch took hold of the land, they established a new village that they called “Noortwyck” (or, North District) because of its position in relation to New Amsterdam. But by 1664, the English had taken Manhattan from the Dutch, and the name was changed to “Greenwich.” Just imagine if the name hadn’t changed… “The Pope of Noortwyck Village,” – it just doesn’t work folks…it just doesn’t pop as much.

It’s Just Greek To Us

By the late 1700s, the land that is now home to Washington Square Park was set aside as a burial ground (for the unknown, poor, and others) and as a venue for public executions. Not so much a ‘family friendly,’ zone.

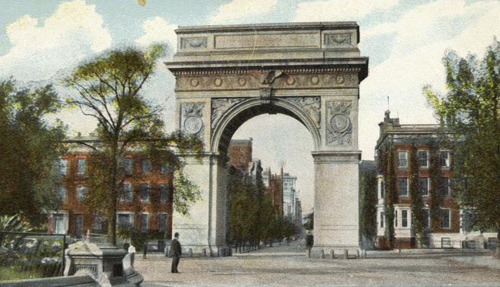

But the area was given new, more desirable designations in the 1820s—as both the Washington Military Parade Ground (a training ground for volunteer militia) and as a public park. Parkland is something that 19th-century Manhattanites were becoming wise-to and excited about, and—as just like today—real estate surrounding any green space started to become highly coveted. The wealthy elite saw Washington Square as a place set apart from the hustle and bustle of “downtown” (commercial activity, plus, most housing of the era was centered in Lower Manhattan).

Stately Greek Revival mansions (in keeping with architectural trends of the day)—punctuated by columns, marble stairs, narrow windows, and pediments (triangular shapes above the windows)—were erected on the park’s north side, on land that once belonged to Captain Richard Randall. The Captain was a successful sailor, and he originally intended that the land be used for a home for aging and disabled sailors. But the organization that was bequeathed the land upon his 1801 death (Sailors’ Snug Harbor) decided that by leasing that land, they’d more easily afford to erect such a gesture/residence on Staten Island, instead. More like Sailors’ Shrewd Harbor!

The Row

Constructed of red brick, this row of attached homes (which came to be known as—wait for it—“The Row”) was erected between 1829-33. Thirteen units in total, and they were rented as single-family residences…and they even served as servants’ homes for the uber-wealthy…those folks living in those fancy Greek digs and mansions and such.

Stables were built along the north side of Washington Mews, directly behind The Row and which made this housing section even more comfortable and convenient – and the notion of servants’ quarters was becoming less and less ‘reasonable.’ The street itself; paved with cobblestone. Prominent businessmen such as Pierre Lorillard (a tobacco manufacturer), Richard Morris Hunt (a prominent architect), John Taylor Johnston (the first president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and their families, soon moved in. The grandmother of author Henry James also lived in The Row—and the setting inspired him to write the novel Washington Square.

By 1854, several stables started to be built along Washington Mews’ south side (adjacent to Washington Square North AKA Waverly Place) as well. These came to serve houses on The Row, and some corresponding stables on the north side were transferred to property owners or renters who lived on West 8th Street.

A Gated Community

A Gated Community

In 1881, New York City's Department of Public Works decided that Washington Mews should be gated on each end—and so, iron gates were installed. This was an effort to deter passersby from wandering down the private mews.

Further changes came in 1916, when Sailors' Snug Harbor decided to remodel twelve of the north-side stables into artist studios. Greenwich Village was attracting more Bohemian sorts—and artists were flocking to this part of town. Edward Hopper, a prominent painter of the ‘20s-‘40s, already lived on The Row (his famous work, Nighthawks, depicts several patrons sitting in a diner late at night).

For this transformative undertaking, Sailors’ Snug Harbor hired Robert Maynicke and Julius Franke. German by birth, Maynicke had trained at Cooper Union; the New York-born Franke had trained at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts (clearly, both architects were both early proponents of “study abroad”).

For this transformative undertaking, Sailors’ Snug Harbor hired Robert Maynicke and Julius Franke. German by birth, Maynicke had trained at Cooper Union; the New York-born Franke had trained at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts (clearly, both architects were both early proponents of “study abroad”).

Maynicke & Franke made their mark with several other projects around town, having designed the International Toy Center (at 5th Ave. and 23rd St.) and 41 Park Row (which was, for a time, the NY Times Building). For the Washington Mews renovation, they used stucco (decorative plaster) and tiles to cover over the brick facades. New windows with window boxes were also installed, and doorways were converted for residential use. The gate at the street’s eastern end was replaced with a brick-and-stucco gateway that boasted lanterns; the western gate was replaced by two posts and a chain.

Funny…when Captain Randall passed away in 1801, his land was yielding $4,000/year in profit (or, $55,000 by today’s standards); by the 1920s, the same land was bringing in profit of over $400,000/year (or $4.6 million today all to Sailors’ Snug (Shrewd) Harbor)—not too shabby!

Filling In The Blanks

Filling In The Blanks

Remaining empty lots of the south side of Washington Mews were filled in during another round of building in the 1930s; ten two-story houses were built to resemble former stables.

Artists found charm in the studio spaces—and notable residents of the 20th century included sculptors Paul Manship (the artist behind the Prometheus statue at Rockefeller Plaza) and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (founder of The Whitney Museum).

Sailors’ Snug Harbor let the last of its leases expire in 1939—and they were courted by real-estate developers who wanted to put high-rises on the Washington Mews property. Ultimately, the organization felt that high-rises would not be an appropriate use for the land which they were gifted by Captain Randall. Around the same time, NYU saw an increase in its student population and had a need for more space near its Greenwich Village campus.

Sailors’ Snug Harbor let the last of its leases expire in 1939—and they were courted by real-estate developers who wanted to put high-rises on the Washington Mews property. Ultimately, the organization felt that high-rises would not be an appropriate use for the land which they were gifted by Captain Randall. Around the same time, NYU saw an increase in its student population and had a need for more space near its Greenwich Village campus.

In 1949, Sailors’ Snug Harbor and NYU came to an agreement that would let the university lease the houses for 203 years (204 years would’ve been pushing it). The buildings have remained mostly unchanged since NYU started leasing them—and today many are used for faculty housing or as language houses. In 1988, NYU hired architect Abraham Bloch to design a new iron gate on the 5th Avenue side, to replace the simple chain. The iron gate was replaced on the University Place side, as well—with brick archways on either side. The street remains private and gated at night (there are padlocks as well as keypad security).

Today, only the eastern half of Washington Mews remains cobblestoned; the western half was paved over with concrete by the 1960s. As for The Row, you may have seen it in the 2007 Will Smith flick, I Am Legend. If you just don’t have any damn time for movies, the historic homes on both Washington Square North and Washington Mews are certainly legendary – and you can just see them in person.

Today, only the eastern half of Washington Mews remains cobblestoned; the western half was paved over with concrete by the 1960s. As for The Row, you may have seen it in the 2007 Will Smith flick, I Am Legend. If you just don’t have any damn time for movies, the historic homes on both Washington Square North and Washington Mews are certainly legendary – and you can just see them in person.

Muse on it!

And then, – wait for it – Mews on it!

Yup…we just did that.

Confetti

COCKTAIL CLASSIC - Tickets are on sale now for the 5th annual Manhattan Cocktail Classic. The city’s most epic cocktail party includes 100,000 cocktails and nearly 100 events over five days in three boroughs, including the epic opening night Gala at the New York Public Library. Spectacular brunches, lunches, tours, soirees, and punch parties await. Get tickets before they’re gone! May 9-13. Various venues throughout NYC. Tickets here.

DOVE PARLOUR - If you’re looking for an experience that’s as decadent as Washington Square Park’s Greek Revival homes, head over to The Dove Parlour for affordable indulgences. With red-velvet wallpaper and a bustling happy hour vibe, The Dove is a cure for all that ails you. Sip a refined cocktail and enjoy dainty, delicious noshes. 228 Thompson Street (between Bleecker & W. 3rd), (212) 254-1435